In the wetland areas of New Jersey, it is not uncommon to hear melodic calls from tree frogs in the evenings of early summer.

Tree frogs are interesting amphibians that have adapted to fill many different roles in their environments. Even though they are rather numerous, you will have a far more difficult time finding them in New Jersey than the “conventional” frogs.

For instance, a tree frog could be right next to your head, yet it might be hiding on the opposite side of a leaf or blend in perfectly with its surroundings.

Around the globe, you may find more than 800 different species of tree frogs. New Jersey is home to just five species of tree frogs, but other states in the United States have as many as sixteen.

In the following article, we’ll go over information regarding the tree frogs that you can discover in the state of New Jersey.

New Jersey’s Resident Tree Frogs

You can often hear tree frogs calling from the marshes of South Jersey in the early summer.

In their collective form, “sticky-fingered frogs” are distinguishable. A mucus-coated disc at the end of their toes allows them to scale vertical surfaces.

The small spring peeper is one such species; its call is among the first signs of spring. In the summer, you may hear the calls of three of the biggest treefrog species: the Gray Treefrog, the Southern Gray Treefrog, and the Pine Barrens Tree Frog.

During the summer, you can find these amphibians on the ground and often high up in trees. They spend the colder months of the year in a dormant state on land, hiding behind logs and leaf litter. However, by the end of spring and the beginning of summer, they congregate in breeding pools in order to mate and deposit their eggs.

New Jersey is home to a variety of tree frogs, including:

1) Northern Spring Peeper

2) Gray Tree Frog

3) Northern Cricket Frog

4) Pine Barrens Tree Frog

5) New Jersey Chorus Frog

1. Northern Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer)

If you’ve lived most of your life in New Jersey’s cities and suburbs, you may not be acquainted with the state’s wildlife. When you think of squirrels, wild turkeys, deer, or frogs, “Spring Peepers” definitely doesn’t spring to mind. It turns out that many of us have really been listening to them for years, either out on the trails or relaxing by the shores of lovely ponds.

The name “Spring Peeper” comes from the sound they make when they chirp, which signals the start of spring. This is a type of small chorus frog. The scientific name for this species is Pseudacris crucifer, and you can find it all throughout New Jersey and the rest of the east coast.

The northern spring peeper is a little tree frog that is more brownish in color and has a characteristic X-shaped cross on its back. Its habitat is in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. It lives in marshy woodlands and places near ponds, marshes, and other bodies of water. The bird’s distinctive “peeping” sound is one among the first indicators that spring has arrived in the area.

Appearance

Peepers may have a variety of colors, including olive, brown, gray, yellow, or any shade in between. This specific subspecies has a belly that is plain or almost completely plain. They have a cross in the form of a black X on their backs, and their bellies are white. This X might be extremely subtle or quite obvious.

It’s possible that females, who are typically lighter in tone, may make it seem washed out. Know this: they are incredibly lovely! The frog has a black stripe running through its eyes as well as dark bands running down each of its legs.

When Peeper makes a sound, its vocal sac expands. In addition to its webbed feet, it has immense, sticky pads on each toe that assist it in ascending trees and climbing other types of vegetation.

Habitat

The Spring Peeper has a habit of gathering in areas where there are bushes and trees that are standing in water. You may find this kind of forest around vernal ponds and marshes, as well as in reclaimed or logged regions.

They live in New Jersey’s forests, marshes, ponds, and swamps. Changing their colors enables them to blend into their surroundings.

Feeding

A variety of small insects, including flies, ants, beetles, and spiders, make up the majority of the spring peeper’s diet.

Voice

The call sounds like a whistle going “peep, peep, peep” over and over again. When there are hundreds of frogs in a chorus, the sound of a single note repeated at clear intervals might be too loud.

During the mating season, males will give out a high-pitched, whistling sound, or “peep,” once per second. When males cluster, such as on muggy nights or immediately following a spring shower, the calling may become more intense

This species’ males are the only ones that chirp, and they do it most often during the mating season, which runs from March to May. Even after the season for mating is through, you can still hear them on stormy evenings.

March is one of the earliest months to hear the call of the spring peeper, which signals early indicators of spring. A male will also make a low trilling whistle if another male gets too near to their calling territory.

Life Cycle & Reproduction

The breeding season for spring peepers runs from March to June and takes place in ponds of freshwater that are fish-free. During the mating season, the most important thing is how the female responds to the male’s call. Male call quality is a factor that females consider while making their mating choice. When it comes to finding a partner, the quicker and more forcefully he calls, the better his chances will be.

The females deposit dozens upon dozens of eggs in the water. Clusters of eggs are stuck to branches and other types of water vegetation. After the mating season has ended, peepers will go into the woods and regions with dense brush. Depending on the temperature, the hatching process might take anywhere from six to twelve days. Tadpoles have gills that allow them to breathe and a tail that helps them swim.

Tadpole tails make it possible for them to grow to be bigger than an adult peeper. As they grow, tadpoles shed their tails in order to develop lungs that allow them to breathe on their own. In 8 weeks or less, tadpoles will have changed into baby frogs and be ready to venture out.

Moreover, they achieve maturity in just a year, reaching their full size by summertime when they have reached their full growth potential. They reach a length of between 1 and 1.5 inches when they are completely mature. Males are generally smaller in size than females.

You should now know everything you need to know to successfully find Spring Peepers in the state of New Jersey. Despite the high-pitched screeching sounds they make, you won’t see these animals very often due to their small size.

Predators

Prey for a wide variety of predatory species, such as owls and other types of birds, snakes, salamanders, and huge spiders.

Spring Peeper Facts

The Chesapeake Bay area is home to a variety of tree frogs, the most common of which is the peeper. They are one of the first species to start mating and calling when spring arrives. These frogs are nocturnal and only come out at night.

The X that may be seen on the back of the spring peeper is not always present in its ideal form, however, it is always visible. The scientific community calls the peeper a crucifer because of its unique trait. The term “crucifix” is where this word comes from.

In spite of the fact that their huge toe pads make them great climbers, northern spring peepers prefer to keep a low profile and stay close to the ground. The vocal sac of the spring peeper is about the size of the rest of the animal’s body.

By producing glucose, these spring peepers prepare themselves for hibernation. Then they go “freezing” themselves. When temperatures rise again, they go back to normal.

2. Gray And Cope’s Gray Tree Frog

Both the Cope’s gray treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and the gray treefrog known as the Northern gray treefrog They are closely related to one another. Their distributions overlap, and they have almost similar appearances and bodies.

The different sounds that these two species make may easily be distinguished from one another. The sound of the Hyla versicolor treefrog is longer and slower, and its pulse rate is about one-half as rapid as that of the cry of the Cope’s treefrog.

This remarkable tree frog is able to gradually alter its color to blend in with whatever it is perched on in order to conceal itself. They might be gray, green, or even brown in color. It is very uncommon for their backs to have a speckled appearance, quite similar to that of lichen.

The gray treefrog is often seen in the northeast, but it lives from Texas to northern Florida and all the way up to Maine and New Brunswick in the north. They love environments that are forested and include trees and shrubs and are located in close proximity to water.

However, the Gray Tree Frog may be found almost everywhere in the state of New Jersey. You may find them in almost every kind of woody environment, from backyards to woods to swamps, and everywhere in between.

Appearance

The Southern gray treefrog is another name for this species. The adults are typically a grayish tint. However, there have been reports of green and brown frogs as well as color variance among individual frogs. Typically, there is a white or yellow dot located just below each eye.

Also, the underside of the hind legs has a golden or orange coloration, and they may or may not have some black speckling. The top portion of the body is murky and warty. Large and rounded, the toe cushions protect the toes.

The female has a white neck, in contrast to the black throat that males have. It’s common for young frogs to have vivid green colors. Tadpoles are easy to identify because of their olive-colored bodies and rust-colored tails. Adults range in length from 1.25 to 2 inches.

The appearance of both of these species of frogs is quite similar to that of the northern gray tree frog. The only way to distinguish between them is by listening to their calls or doing chromosomal research. The cry of the southern gray treefrog, which is a booming trill, is both quicker and higher in pitch than the call of the northern gray treefrog.

Habitat

The only places in New Jersey where you may find the southern gray treefrog are in Cape May, Cumberland, Atlantic, and Ocean counties. The majority of this region’s population may be found in the southern part of Cape May County.

Throughout the mating season, southern gray treefrogs come down to the water’s edge from the trees. During the rest of the year, they spend most of their time there.

During the breeding season, the most popular places for them to call are bare horizontal branches that are located above water. They are born in bogs or vernal ponds, but spend the remainder of the year in the mixed forests that are found at higher elevations. Outside of the time of year when they are reproducing, males of this species of treefrog will regularly call on days that are warm and wet.

Throughout the whole of their annual cycle, southern gray tree frogs need the presence of old fields, hardwood forests, and small freshwater ponds. They may be seen breeding in a broad range of basins, both natural and man-made. To prevent predatory fish from forming in breeding pools, the water must drain before the end of summer. Ponds used for breeding are often situated inside or in close proximity to mixed or deciduous woods, such as climax oak/pine forests.

Feeding

Southern gray tree frogs sleep all day and seek food at night. Their diet consists of insects and spiders. They consume flying insects in addition to those that might be discovered concealed in the branches and foliage. The diet includes flies, mosquitoes, gnats, spiders, and ants, in addition to numerous types of insects and the larvae of other types of insects. The tadpoles consume algae that is native to the ponds in which they were born.

Voice

The thrill of the Northern Gray Treefrog is long and drawn out, but the thrill of the Southern Gray Treefrog is much shorter, more rapid, and tuned higher. When the temperature drops, the trills of both species are performed at a more leisurely pace. A recording of the call, together with temperature and humidity, can help identify species when their ranges overlap. This is because it is difficult to differentiate between the two in these areas.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

In April and May, southern gray tree frogs sing when nighttime temperatures are over 63 degrees Fahrenheit. Even though they may sing from late April all the way through the middle of August, the best choruses are during the warm and humid nights of May and June. Males will emit calls from the ground, bushes, or trees in order to coax females to congregate in mating ponds.

In a breeding pond, the female lays her eggs individually or in clusters of up to 40 on the leaf litter and aquatic vegetation. After that, the male is responsible for fertilizing the egg masses. In the course of one season, the female will have deposited a total of over 2,000 eggs.

If a female lays her eggs singly or in little clusters, they are less likely to be damaged by predators or drying out. In four to five days, the eggs will hatch, and the whole transformation will take between 80 and 100 days. After they have emerged from their eggs, the newborn frogs immediately disperse into the adjacent fields and woods.

Adult tree frogs go to the terrestrial habitats in the area around their breeding ponds during the months of July and August. They spend the winter here, either in the cavities of trees, under the bark, or in subterranean burrows, which is where they often make their homes. Their blood includes an “antifreeze,” making them immune to freezing and thawing.

Current Dangers, Status, And Preservation

Biologists have spent the past 20 years researching the southern gray treefrog in New Jersey. At this time, efforts are being done to conserve tree frog habitats on both a landscape level and on an individual wetland basis. These efforts are now underway. New Jersey’s land use laws preserve breeding ponds and their 150- to 300-foot buffer zones.

Southern gray treefrog in New Jersey are threatened due to the destruction of forest ponds and woods. Small vernal pools are subject to illicit filling. Even though wetland regions are protected, many upland ecosystems are at risk. Tree Frogs can only complete their life cycle in an environment that has both wetlands and neighboring woody uplands.

Moreover, loss of habitat is often accompanied by a deterioration in the grade of the water supply, since the runoff, effluent from wastewater treatment plants, leaching of harmful chemicals, and illegal dumping may all poison ponds.

It’s possible that predators in breeding ponds may reduce treefrog numbers by eating treefrog eggs and larvae. The mosquito fish that are introduced into ponds in order to reduce the number of mosquitoes also eat on the eggs and larvae of these tree frogs.

Authorities should build additional breeding ponds within the same wetland complex since the southern gray treefrog may travel between ponds. This is both a long-term need for the species and its natural behavior. Management must involve preserving wetland regions surrounding inhabited ponds to maintain healthy populations. This will give the animals more places to live and keep genetic diversity. This is necessary in order to ensure that populations may continue to exist.

In places where the southern gray treefrog lives, man-made ponds may be built for breeding. Man-made ponds may enhance habitat, but they shouldn’t replace natural ponds. The preservation of habitats needs to take precedence over all other concerns.

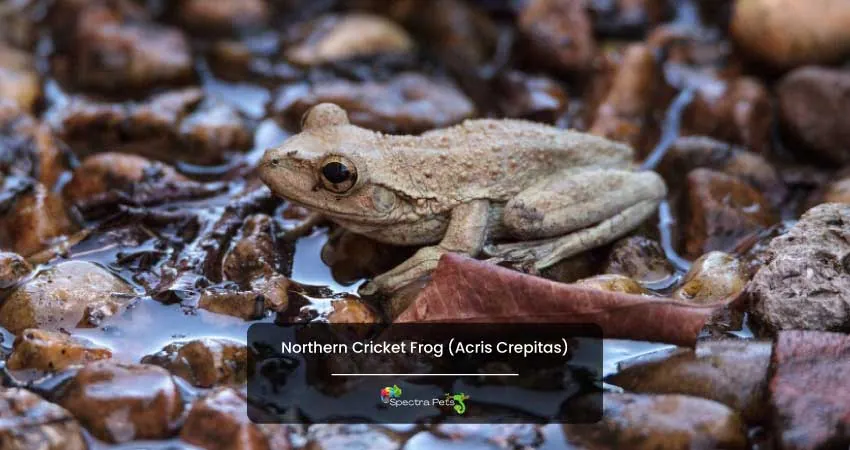

3. Northern Cricket Frog (Acris crepitas)

The Northern Cricket Frog is a species of little frog that you can easily find close to ponds, lakes, and streams that move slowly. This species is common in Tennessee and you can easily find them throughout the state of New Jersey with the exception of the highest areas of the eastern highlands.

Appearance

This species’ coloring and patterning is quite diverse, and its size ranges from around 5/8″ to 1 1/2″. There is a black mark in the form of a triangle located in the middle of its eyes. There is also a dark stripe that runs up the back of the thigh. It has rough, warty skin, and the webbing on its rear feet goes all the way to the tips of its toes.

It sounds like a cricket and has a rhythmic, clicking sound that goes like this: gick, gick, gick, gick, etc. It starts off softly but then quickly builds up the pace.

Habitat

This species’ range extends all the way up to the southeast corner of New York state in the north. After then, its range expands to the southwest across New Jersey and along the Appalachian Mountains and Piedmont area.

Then it continues to stretch to the southwesterly direction all the way to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas. It’s found from New Jersey to southern Virginia along the Atlantic Coast, but not in North, South, or Georgia. Only the western part of Florida’s panhandle has any signs of its presence inside the state.

With the exception of the central Pinelands, this species may be found across the whole of the state of New Jersey.

The habitat of this species includes marshes, ponds, and slow-moving streams.

Feeding

The larvae will consume organic waste, algae, and plant tissue that is floating in the water as their food source. Small invertebrates that may be discovered in or near the water are the adults’ primary food source.

Voice

The sound of the call is comparable to that of two tiny stones being tapped together. The tapping has a sluggish beginning, then it picks up the pace, and then it goes back to being slow. It is possible to hear them calling from March all the way through July, but often the calling begins in April and reaches its height in May.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

There could be hundreds of eggs produced by this particular species. The larvae spend their formative stages in the shallow water of ponds, marshes, ditches, sluggish streams, or vernal pools throughout the spring and summer. During the summer, the aquatic larvae develop into adult forms. After one year, they have reached the age of sexual maturity.

This species exhibits diurnal (daytime and nighttime) activity throughout the warmer months. On the other hand, when the temperatures are lower, they could only be active during the daylight. They spend the winter underground, usually in close proximity to water and sometimes in small groups. They may continue to be active during winters that are rather mild.

Current Status, Threats, And Conservation

This species may be found all across the state of New Jersey. However, their numbers have been on the decline recently and their population has to be monitored. The loss or destruction of this species’ habitat poses the biggest risk to its survival.

Northern Cricket Frog Facts

Their lifetime is just around four months on average. Within a period of six months, populations may undergo total turnover. They spend much of their time active throughout the day and may often be seen sunbathing in groups in sunny areas.

The Northern Cricket Frog is capable of jumping more than three feet. In order to avoid being caught by predators, it often hops in a zigzag pattern.

4. Pine Barrens Tree Frog (Hyla Andersonii)

The Pine Barren tree frog among the small creatures you might see in the warm nights of June in New Jersey. It became a symbol of the Pine Barrens in New Jersey. It is so small that it can sit on a leaf.

Appearance

The adult Pine Barrens treefrog has an emerald green body with a white border and a purple or plum tint. The underside of the hind legs is yellow to orange. The length of an adult’s snout to vent ranges on average from 2.8 to 4.3 centimeters (1.1 to 1.7 in.).

Tree Frogs can climb very well because the tips of their fingers and toes have “suction cups” that hold them in place. Tree frogs’ honking sounds come from their noses. Even though they start calling in April and may do so until August, the best time to hear them is in May and June.

Habitat

Many people regard the Pine Barrens treefrog as a symbol of the whole Pinelands habitat, however, it’s only found in New Jersey. They live in the area from the southern tip of Alabama to the panhandle of Florida. You can also find them in the sandhills of North and South Carolina.

These tree frogs live in a broad range of natural environments across the state of New Jersey. Some of these environments include wet areas in pitch pine lowlands, intermittent streams, and ponds. You may also find them in streams, seeps, sphagnaceae bogs, and isolated ponds.

They also live in cranberry bogs, stream impoundments, automobile ruts, borrow pits, and roadside ditches. Some of these frogs prefer early successional, shrub- and herbaceous-dominated pondlike settings.

However, they do not often exist in large numbers in ecosystems that are home to fish, such as impoundments, permanent ponds, and streams. Typical characteristics of ideal breeding ponds are their seclusion, shallowness, dilution, and acidity (e.g., pH 3.74 – 4.69). It’s possible that shrubs will just grow along the pond’s edge, allowing some space for open water, or they may take over the whole space.

Feeding

The Pine Barrens tree frog consumes a wide variety of insects for food. From its nesting grounds, it will travel a distance of up to 345 feet (105 meters) to eat (Means 2005).

The majority of the food nutrition for adult Pine Barrens tree frogs comes from tiny insects. This includes any insect, from grasshoppers and crickets to spiders, flies, and and beetles. Tadpoles ingest algae, small invertebrates, and watery plants.

Voice

From April through September, Pine Barrens tree frogs call. Males call from the ground, shrubs, or nearby foliage. Their call repeats 10 to 20 times at random intervals and sounds like a nasal “honk” or “quonk.”

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Pine Barrens tree frogs will typically lay their eggs between the months of May and June. The tadpoles will develop into adults between the months of July and August.

One study found that most tree frogs remain within 70 meters (230 feet) of the mating area during the breeding season. However, these tree frogs have been heard calling from distances of more than 100 meters (328 ft.).

Treefrogs relocate and call from stations that are farther distant from the nesting site as the breeding season comes to a close. Early in May, as temperatures and precipitation rise, males call more often.

Evenings in June, when the temperature is warm and the humidity is high, see the highest levels of vocal activity. It is possible for the males to sing sitting on the ground or from among the bushes close to the mating pond.

During mating months, Pine Barrens tree frogs hide in the daytime and eat at night. They usually hide among the ground cover or perched high in the trees. Some of them may call until the middle of July, nevertheless, they usually stop calling as soon as July begins.

Female tree frogs will only deposit one egg at a time in order to reduce the possibility of losing the whole clutch at once. After finishing the process, a single female has the potential to lay up to 1,000 eggs. The male will fertilize the eggs regardless of the situation. Within 1 to 2 weeks, these eggs might develop into tadpoles.

Within 80 to 100 days, tadpoles become froglets, depending on the weather conditions and the amount of rainfall. Fat stores in the froglets’ tails ensure their survival up to the time they are mature enough to go out and find food for themselves.

After undergoing metamorphosis, young frogs spread into areas such as bogs, forests, & wet meadows. Once the process of reproduction finishes, adult tree frogs migrate to nearby forests and stay for the rest of the year.

Current Threats, Conservation, & Current Status

New Jersey listed the Pine Barrens treefrog as an endangered species since 1979 owing to the fact that its range was severely limited, its population was steadily dropping, its habitat was being destroyed, and breeding ponds were being polluted.

Due to the fact that the population of these tree frogs inside New Jersey is thought to be stable at the present time, its range within the state is protected. It’s possible that they’re numerous in locations where the ecosystem is ideal. Nevertheless, this species must be conserved since the habitat it relies on is restricted to specific Pine Barrens sites that are only patchily scattered across the species’ range.

The most significant threats that these Pine-Barrens treefrogs face in the state of New Jersey are the destruction of their habitat, the draining, and filling of wetlands, pollution, and rises in the pH level of the water.

Wetlands of high quality have been degraded and eliminated throughout the state as a direct consequence of unrestrained development, which has spread over the state’s whole range.

Loss of habitat degrades the quality of water and raises pH levels, which benefits these tree frogs’ enemies.

These factors include pollution and a sinking water table. Pine Barrens treefrogs are ecologically sensitive and have a fragmented population.

Due to the fact that these special tree frogs favor acidic water, pH changes can prevent Pine Barrens treefrogs from reproducing or developing their larvae.

Both juvenile and adult Pine Barrens treefrogs are often preyed upon by bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana), which is more likely in areas where the pH levels are higher.

Due to the fact that it has a delayed breeding season, these tree frogs are particularly susceptible to being eaten by the tadpoles of species that have an earlier breeding season.

5. New Jersey Chorus Frog (Pseudacris Kalmi)

New Jersey Chorus Frog is one of the most common frog in the woods of New Jersey.

Appearance

New Jersey chorus frog and upland chorus frog are very identical (Pseudacris ferarium). The greatest approach to differentiate between the two is by listening to their different vocal ranges. According to a recent study, all of the populations in New Jersey are composed of New Jersey Chorus Frogs. They are also known as Pseudacris kalmi.

This species may range in hue from brown to gray and can be anywhere from 0.4 to 1.2 inches in length. There is a bright stripe that runs down the top lip, and there is also a black stripe that goes through the eye and down the side of the body. The abdominal region is whitish.

Moreover, a black triangle may be present between the eyes, similar to how it is on the upland chorus frog. These patterns, which run down the back in three thick, black stripes, are darker on the New Jersey chorus frog than on the upland species.

Habitat

This species may be found in the Delmarva Peninsula, which includes eastern Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. They are also seen in the state of New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania. In New Jersey, it’s most common in the south and east, but not in the Pinelands. The region of the state’s northwest where the upland chorus frog may be found the most often is the far northwest.

This species inhabits grassy floodplains, wet woods, and shallow wet woodlands (marshes, ditches, swamps, or vernal pools). Floral-rich ponds, meadows, and woods are more suitable for their habitation. During the mating season, it may be found in bodies of water that are either temporary or permanent.

Feeding

The larvae will consume organic waste, algae, and plant tissue that is floating in the water as their food source. Adult frogs consume several types of tiny invertebrates for food.

Voice

It sounds like someone is brushing their fingers over the teeth of a comb—creek or prreep.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Late in the winter, mating starts, and it lasts all the way through June. In ponds, marshes, ditches, slow streams, or vernal pools, the eggs adhere to submerged plants. The larvae then grow in these areas. In the late spring, the aquatic larvae transform into their adult forms.

Current Status, Threats, And Conservation

This species may be found all across the state of New Jersey. However, their numbers have been on the decline recently and their population has to be monitored. The loss or destruction of this species’ habitat poses the biggest risk to its survival.

Frequently Asked Question

Which tree frog is the most common in New Jersey?

The gray treefrog is the most frequent and widespread species in the state. They are less than two inches in length and have warty, mottled gray skin.

Even yet, they are capable of gently altering their color to adapt to their environment, you can easily find them in a wide range of hues, from green to almost black.

Where do the frogs in New Jersey spend the winter?

The toad will dig a hole in the earth rather deep during the winter, far below where the ground would freeze. Toads will dig their burrows deeper into the earth when the frost line moves farther away from them. They are distributed across the whole of the northern area, with the exception of Monmouth County in the state of New Jersey.

Does New Jersey have poisonous frogs?

The only poisonous frog that lives in New Jersey is the Pickerel Frog. When they are attacked, they give off poisonous skin irritations that can kill other animals and may give people skin irritations if they touch them. As you might guess, most predators don’t bother them.

Final words

New Jersey is home to a number of tree frogs, which have been discussed throughout this article. You’re already familiar with the characteristics that’ll help you recognize them, right? Now, if you want that natural outdoorsy vibe in your home, you may also borrow one.

Tree Frogs Found in the Nearby States of New Jersey: