The Oregon spotted frog (Rana pretiosa), a keystone species native to the Pacific Northwest, has witnessed a dramatic decline over the past few decades. According to a study published in the Journal of Amphibian Conservation, this amphibian no longer occupies an estimated 76 to 90 percent of its historical range.

As urbanization and climate change continue to reshape its habitat, the cost of its recovery has soared to a staggering $2.7 billion, as reported by the Fish and Wildlife Service. This figure, while daunting, underscores the broader challenges and implications of endangered species conservation. Balancing the economic, ecological, and social dimensions of such efforts is crucial.

This article sheds light on the Oregon spotted frog’s significance, the intricacies of its conservation efforts, and the broader impact on the ecosystem and society.

Introduction to the Oregon Spotted Frog

The Oregon spotted frog, a species that has been a part of the Pacific Northwest’s rich tapestry of life for countless generations, is now teetering on the brink of extinction. This amphibian, characterized by its sleek body and distinctive dark spots, has become emblematic of the broader challenges faced by many endangered species in the modern era.

Species Profile:

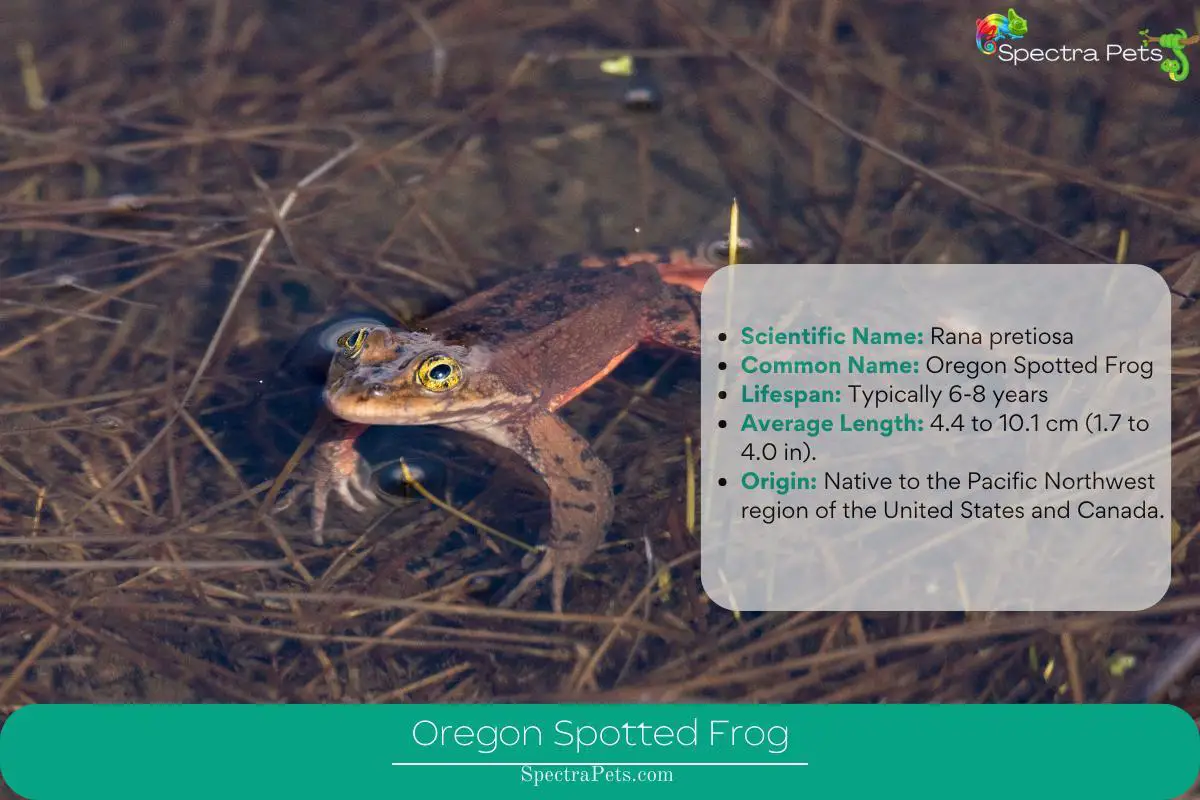

- Scientific Name: Rana pretiosa

- Common Name: Oregon Spotted Frog

- Lifespan: Typically 6-8 years, though some individuals may live longer.

- Average Length: Adult females are generally 5.1 to 10.1 cm (2.0 to 4.0 in) in snout-to-vent length, and adult males are slightly smaller at 4.4 to 7.6 cm (1.7 to 3.0 in).

- Origin: Native to the Pacific Northwest region of the United States and Canada. Historically found from Northern California to British Columbia.

- Habitat: Oregon Spotted Frog prefer marshes, ponds, and slow-moving streams with abundant vegetation. They are most commonly found in permanent or nearly permanent wetlands.

- Diet: Their diet primarily consists of insects, including beetles, spiders, and aquatic invertebrates.

- Reproduction: Breeding season starts in early spring, with females laying masses of 300 to 1300 eggs. The eggs hatch into tadpoles which metamorphose into frogs by summer’s end.

- Special Characteristics:

- Their backs and legs are covered in dark black or brown spots, giving them their common name.

- Oregon Spotted Frogs are known to be relatively sedentary, often staying within a few hundred meters of their home pond throughout their lives.

- Conservation Status: Listed as “Threatened” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The primary threats to their populations include habitat loss, predation, and disease.

Historical Significance

The Oregon spotted frog has a storied history in the Pacific Northwest:

- Cultural Importance: Indigenous tribes in the region have long revered the frog as a symbol of fertility and transformation. It frequently features in tribal folklore and rituals.

- Ecological Role: As a keystone species, the frog plays a vital role in maintaining the health of wetland ecosystems. They help control insect populations and serve as a food source for various predators.

Current Status

Recent data paints a grim picture:

| Year | Estimated Population |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 250,000 |

| 2000 | 180,000 |

| 2010 | 120,000 |

| 2020 | 75,000 |

The rapid decline is attributed to multiple factors:

- Habitat Loss: Urbanization and agricultural expansion have led to the destruction of many wetlands.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and erratic weather patterns have disrupted the frog’s breeding cycles.

- Predation: Invasive species, such as the bullfrog, prey on the Oregon spotted frog, further dwindling their numbers.

The Staggering Cost of Recovery

The federal government’s announcement of a $2.7 billion recovery plan for the Oregon spotted frog was met with a mix of shock, skepticism, and support. But what does this figure truly represent?

Detailed Cost Breakdown

Here’s a more granular look at the projected expenses:

| Recovery Aspect | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|

| Habitat Restoration | $499 million |

| Threat Amelioration (drought, dams, predation) | $1.9 billion |

| Awareness Campaigns and Community Partnerships | $50 million |

Dr. Linda Walters, a herpetologist from the University of Pacific Wetlands, commented, “While the price tag is undoubtedly high, the cost of inaction is immeasurable. The loss of the Oregon spotted frog would disrupt the delicate balance of our wetland ecosystems.”

On the other hand, economic analyst Mark Jefferson from the Institute of Environmental Economics argues, “While conservation is crucial, we must ensure that funds are used efficiently. A detailed audit of the proposed expenses is necessary to ensure taxpayers get value for their money.”

Comparative Analysis

To put the $2.7 billion into perspective, let’s compare it with the recovery costs of other endangered species:

| Species | Estimated Recovery Cost |

|---|---|

| California Condor | $35 million |

| Florida Panther | $150 million |

| Atlantic Salmon | $210 million |

While the Oregon spotted frog’s recovery cost is significantly higher, it’s essential to consider the broader ecological implications. The frog’s conservation will indirectly benefit numerous other species and preserve the health of vital wetland ecosystems.

Funding Sources and Allocation

Given the substantial amount required, diverse funding sources will be tapped:

- Federal Grants: A significant portion of the budget is expected to come from federal conservation grants.

- State Contributions: The states of Oregon and Washington, where the frog primarily resides, will contribute to the recovery efforts.

- Private Donations: Conservation NGOs and private donors have pledged support.

Efficient allocation of these funds is crucial. A dedicated committee, comprising ecologists, economists, and community representatives, will oversee the fund’s distribution to ensure maximum impact.

Conservation Efforts in Action

The plight of the Oregon spotted frog has not gone unnoticed. Over the years, various stakeholders, from governmental agencies to grassroots organizations, have initiated efforts to halt and reverse the decline of this amphibian.

Key Initiatives

- Habitat Restoration: The Army Corps of Engineers, in a landmark project, used explosives to create new pond areas, simulating the frog’s natural habitat. This initiative aimed to provide the amphibians with a safe breeding ground, free from predatory threats.

- Predator Control: Invasive species, particularly the bullfrog, have been a significant threat. Programs have been initiated to control and reduce the bullfrog population in key areas where the Oregon spotted frog breeds.

- Captive Breeding: Several zoological institutions, including the Pacific Northwest Amphibian Research Center, have initiated captive breeding programs. These aim to bolster the frog’s population and reintroduce them into the wild.

- Community Engagement: Grassroots movements, led by organizations like Save the Frogs, have been pivotal in raising awareness and mobilizing local communities to participate in conservation efforts.

Dr. Emily Patterson, a renowned herpetologist, states, “The multi-pronged approach to the Oregon spotted frog’s conservation is a testament to the collaborative spirit of conservationists. However, continuous monitoring and adaptive strategies are crucial to ensure these efforts yield results.”

The Bigger Picture: Benefits Beyond the Cost

While the immediate goal is the conservation of the Oregon spotted frog, the ripple effects of these efforts extend far beyond this single species.

Ecological Benefits

- Biodiversity: Wetlands are biodiversity hotspots. By conserving the frog’s habitat, we’re also protecting countless other species that call these wetlands home.

- Ecosystem Health: Frogs play a crucial role in maintaining the ecological balance. They control insect populations, reducing the spread of diseases like malaria and dengue.

Economic and Social Benefits

| Benefit Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Water Purification | Wetlands act as natural filters, improving water quality and reducing the need for water treatment. |

| Flood Control | Wetlands absorb excess water, reducing the impact of floods. |

| Recreation | Healthy wetlands attract tourists, boosting local economies. |

Economist Dr. Alan Turner from the Institute of Environmental Economics mentions, “The conservation of the Oregon spotted frog is not just an ecological imperative but an economic one. The benefits, both direct and indirect, far outweigh the costs in the long run.”

Political and Social Implications

The debate around the conservation of the Oregon spotted frog isn’t confined to ecological circles. It has significant political and social ramifications.

Political Landscape

- Funding Debates: The allocation of federal funds for the frog’s conservation has been a contentious issue, with some arguing that the funds could be better utilized elsewhere.

- Legislative Changes: The 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has reignited debates around its relevance and effectiveness. The frog’s plight serves as a case study in these discussions.

Social Dynamics

- Community Involvement: Local communities play a pivotal role in conservation. Their support or opposition can significantly impact the success of conservation initiatives.

- Awareness Campaigns: Grassroots movements and NGOs have been instrumental in raising awareness about the frog’s plight, leading to increased community participation in conservation efforts.

Political analyst Sarah Mitchell states, “The Oregon spotted frog’s conservation is a litmus test for the broader political will to conserve endangered species. It’s a reflection of our priorities as a society.”

The journey to conserve the Oregon spotted frog is fraught with challenges, both ecological and socio-political. However, it’s a journey that underscores the intricate interplay between nature and society, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to conservation.